What a situation! Picture us standing there on the roof of Parking 58, finding our way with a map of the park of Versailles in our hands. Picture this large surface of concrete through which we have to stretch a path. Headphones on our ears, booklet in our hands. While there is so much to see and hear up there, high in the sky. A bit complicated for common Handlers – pardon: Trainees – as you and me.

To get lost is fun. That we know. The Situationists knew that too. The Doctor told me about them. She explained me that in the fifties and sixties, they searched for more structured and less complicated ways to get lost in the city. To use a map of London in order to find your way through Paris, for example. The difference was that the Situationists had an eye for the city in which they got lost. To get lost was part of the discovery. The Doctor taught me all that. But there is not so much to discover on a parking lot when you only have eyes for the booklet in your hands and ears for the headphones on your head.

Very serious rules are then becoming a little game. A number. A track.

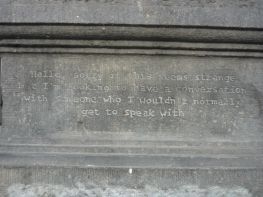

Brussels Tracks is the name of – take a deep breath – An experimental and performative audio guide for the city of Brussels. It is a project by David Helbich. In an interview he talks about his inspiration from the Situationists. Or from Star Trek. Holodeck, please, one of the tracks in his guide, is quite beautiful in all its simplicity. All you have to do is stand at the balustrade of the parking, think that you are on the Holodeck of Star Trek, and look out over the city of Brussels while listening to the sounds of the city of Nablus. You hear chants, the echo of the mountains, pure poetry.

These moments are rather rare in Brussels Tracks. You spend more time finding your way through instructions from the booklet, sounds from the headphones and the interface of the MP3-player. We spent quite some time at City2 because none of us knew how to change the volume. Sweeping to the left or to the right. Very simple, but you have to know.

Here is a list of things, Odile, to remember for our final presentation:

– keep things simple

– do not cut your work in tracks, but present them as much as possible as a whole

– limit instructions to clear and simple rules

– give rules before you start so you can forget them once you start working

– use media only when strictly needed

– search for user friendly tools

– think about your environment: keep it as large as possible

– focus you attention on your environment and not on the instructions

– make participants feel comfortable, protect them, don’t put them on display, but allow them to look with you

– leave room to explore without determining in advance what is important

Ah, where is Ant Hampton when you need him, Odile?

Goodbye Odile!

Kiss,

Odile